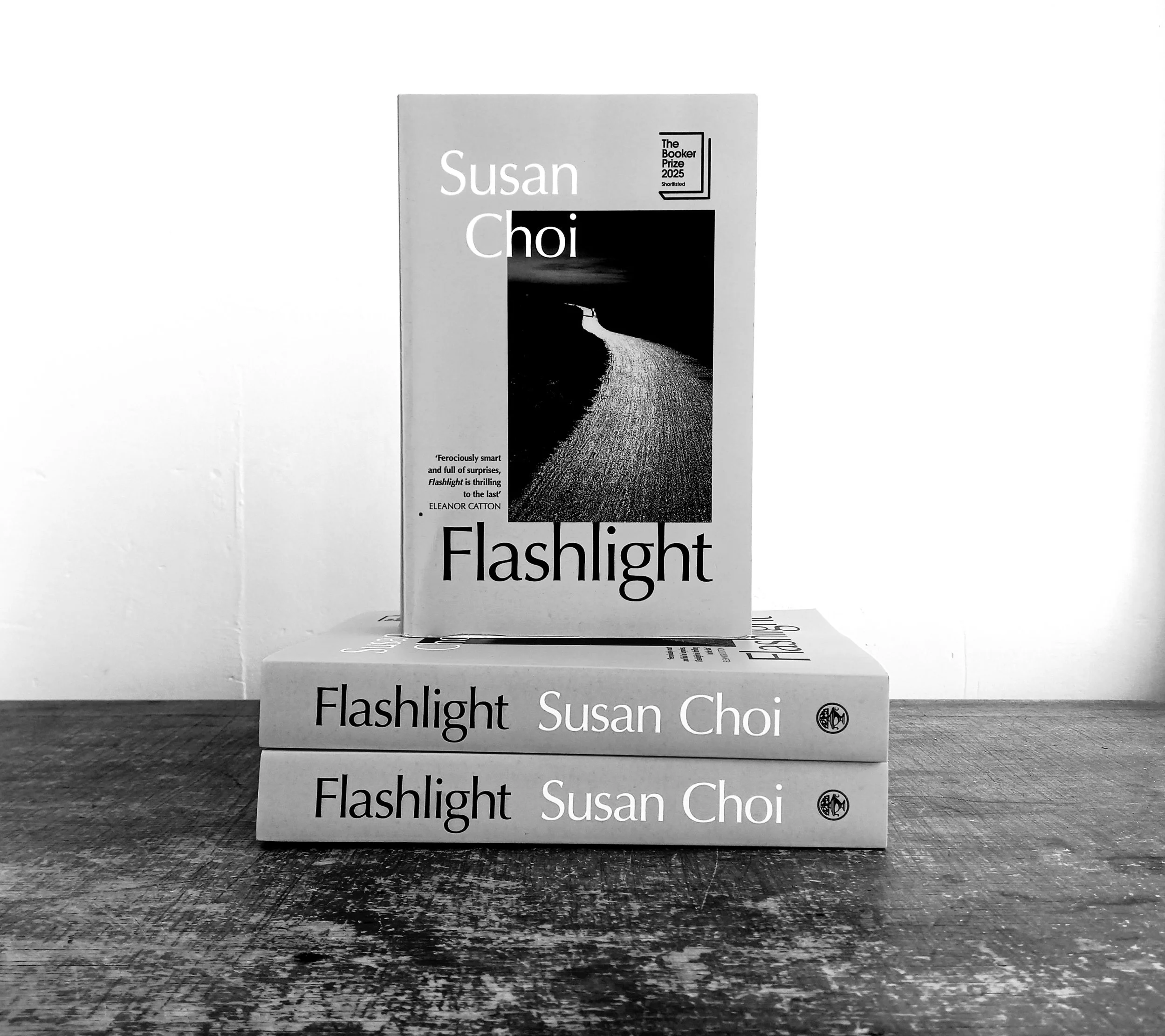

“Flashlight is a sprawling novel that weaves stories of national upheavals with those of Louisa, her Korean Japanese father, Serk, and Anne, her American mother. Evolving from the uncertainties surrounding Serk’s disappearance, it is a riveting exploration of identity, hidden truths, race, and national belonging. In this ambitious book that deftly criss-crosses continents and decades, Susan Choi balances historical tensions and intimate dramas with remarkable elegance. We admired the shifts and layers of Flashlight’s narrative, which ultimately reveal a story that is intricate, surprising, and profound.” —Booker Prize judges’ citation

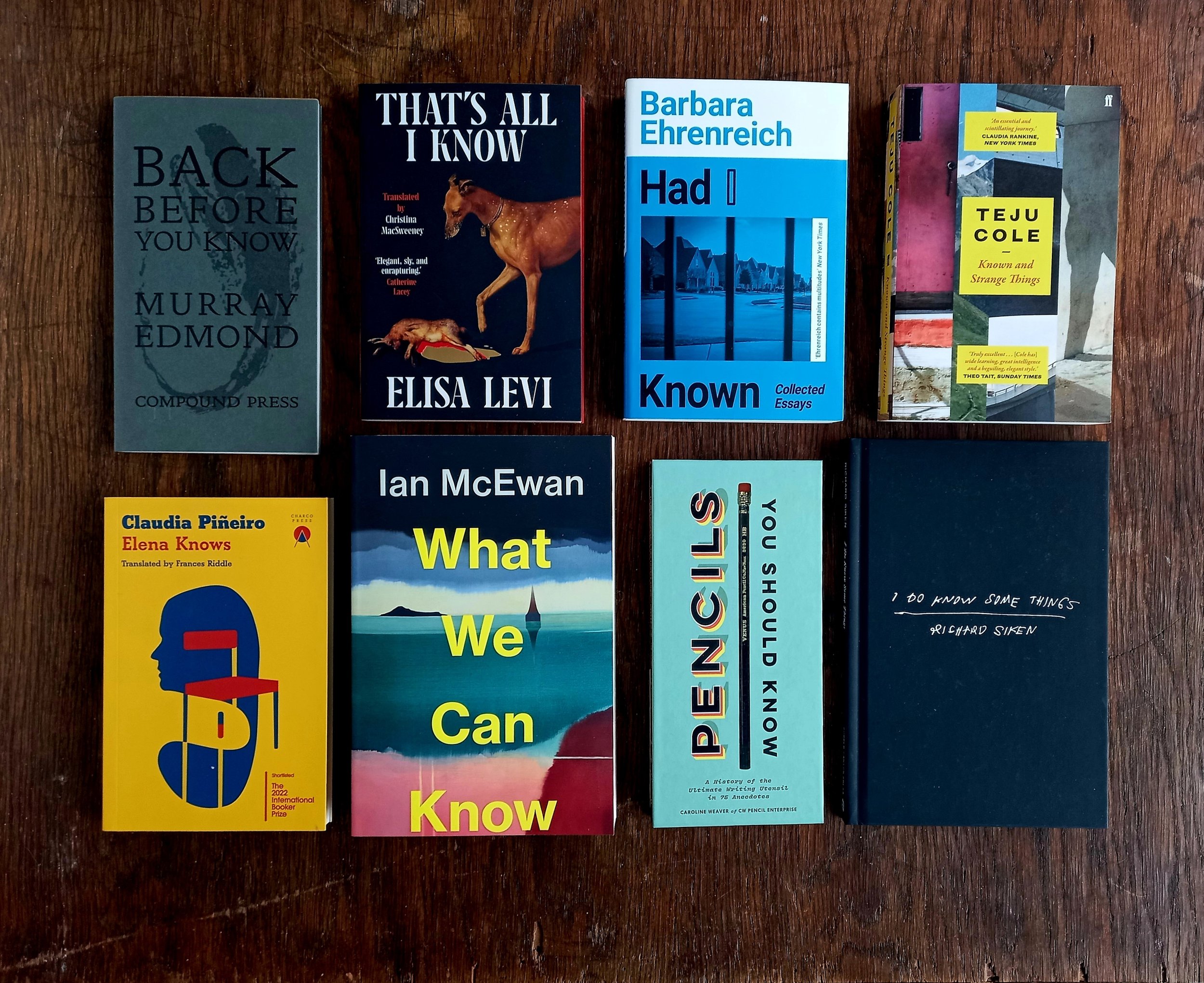

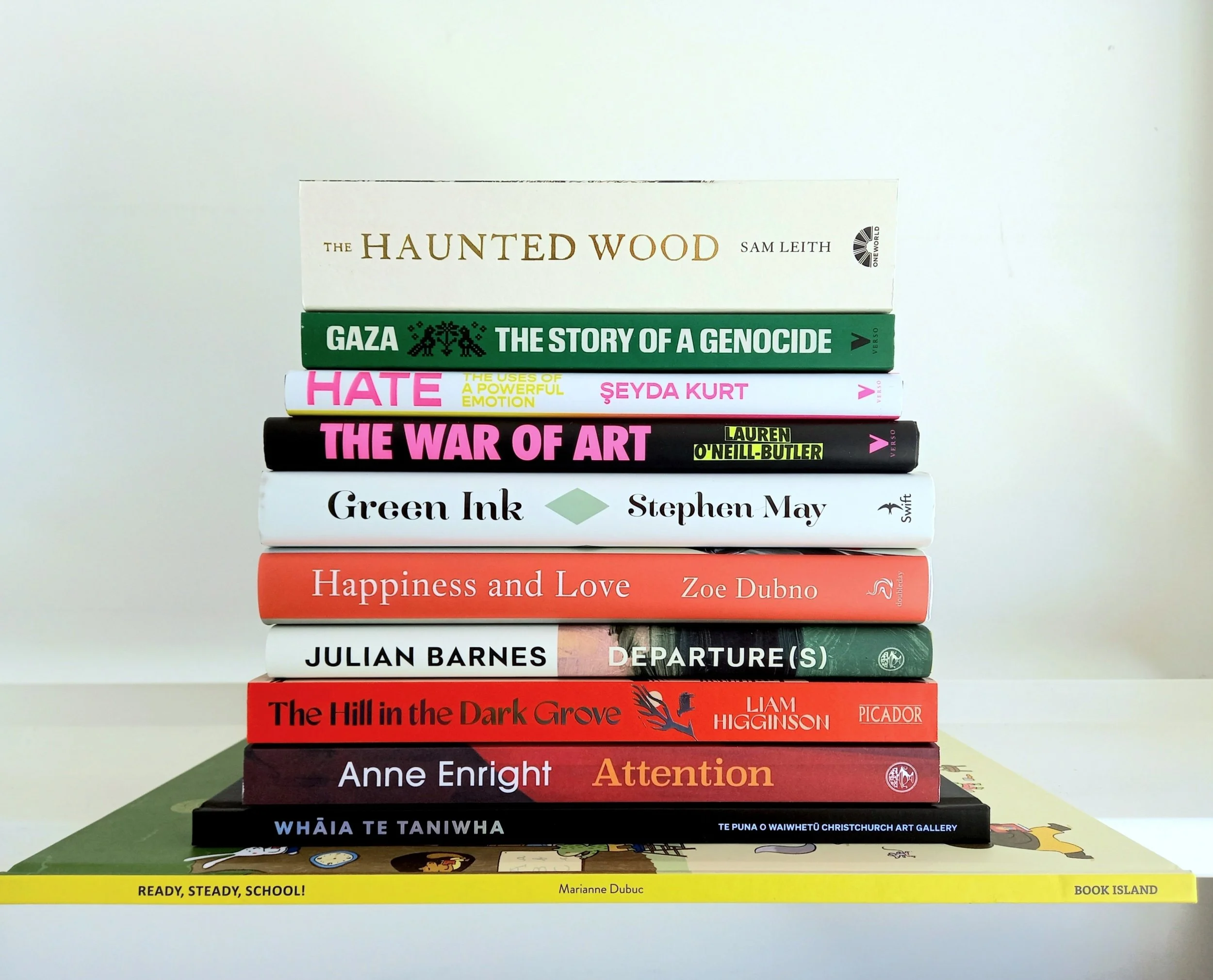

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

All your choices are good! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

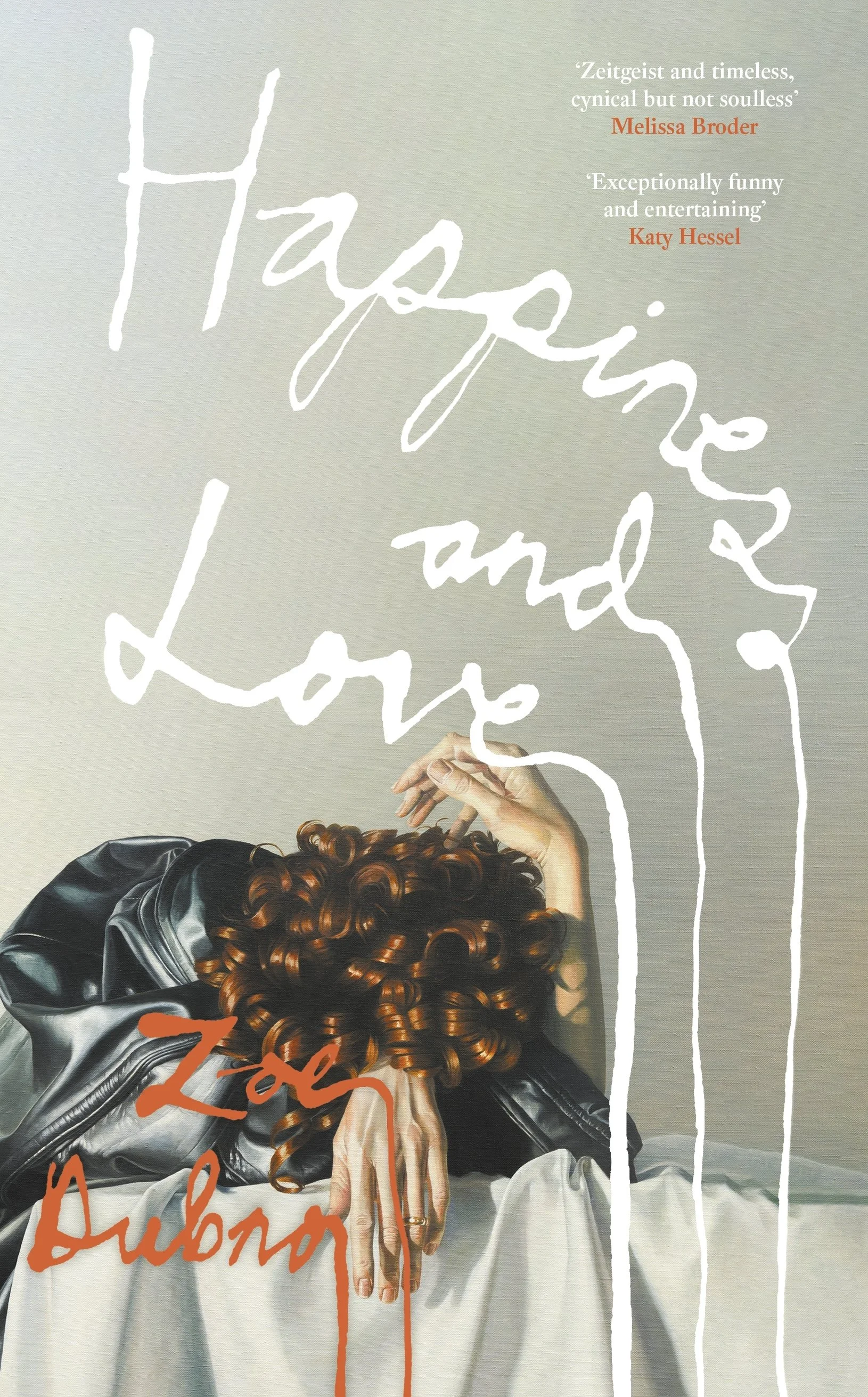

Happiness and Love by Zoe Dubno $38

An unnamed narrator who has fled a set of friends she despised, who bring out the very worst in her and each other, finds herself once more sat at their dinner table for a single, hideous evening. Years after escaping her unbearable artworld friends in New York for a new life in London, an unnamed writer finds herself back on the Lower East Side attending a dinner party hosted by Eugene and Nicole — an artist-curator couple — and attended by their pretentious circle. It's the evening after the funeral of their mutual friend, a failed actress, and if the narrator once loved and admired Eugene and Nicole and their important friends, she now despises them all. Most of all, however, she despises herself for being lured back to this cavernous apartment, to this hollow, bourgeois social set, for a dinner party that isn't even being thrown in their deceased friend's honour, but in the honour of an up-and-coming actress who is by now several hours late. As the guests sip at their drinks and await the actress's arrival, the narrator, from her vantage point in the corner seat of a white sofa entertains herself — and us — with a silent, tender, merciless takedown. [Hardback]

”As observant as a sniper, and just as ruthless, Zoe Dubno in Happiness and Love pulls off an unlikely yet ultimately very successful literary metempsychosis. Bernhard's fierce sarcasm and disappointment resonate very clearly in her voice; despite the distance that separates his 1980s Vienna from her contemporary New York, Dubno shows us — at times comically, at times despairingly — that the superficiality, hypocrisy, and flatness never change.” —Vincenzo Latronico

”Zoe Dubno examines character and human relations in the same way an art critic looks at a painting. Digging deeper and deeper into the thoughts behind thoughts, feelings behind feelings and questioning everything, Happiness and Love is an ecstatic performance of heightened perception.” —Chris Kraus

>>Read Stella’s review.

>>Cutting wood in New York.

>>The book is ‘based’ on Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters.

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes $38

Departure(s) is a work of fiction — but that doesn't mean it's not true. Departure(s) is the story of a man called Stephen and a woman called Jean, who fall in love when they are young and again when they are old. It is the story of an elderly Jack Russell called Jimmy, enviably oblivious to his own mortality. It is also the story of how the body fails us, whether through age, illness, accident or intent. And it is the story of how experiences fade into anecdotes, and then into memory. Does it matter if what we remember really happened? Or does it just matter that it mattered enough to be remembered? It begins at the end of life — but it doesn't end there. Ultimately, it's about the only things that ever really mattered — how we find happiness in this life, and when it is time to say goodbye. [Hardback]

”A moving, engaging book. Barnes’s humorous narrative explores the effect of time on love. A rather lovely swansong.” —Independent

”An elegant, thoughtful final book, which considers old age, fate and happiness. It's an arch blend of memoir and make-believe — and rather touching.” —The Times

”A richly layered autofiction. Artfully constructed to seem casually conversational, it braids erudite essayism and fiction, and every line is turned inside out with qualifications.” —Observer

”At a little over 150 pages, Departure(s) is brief but it is not slight and, each time I read it, I thought about it for days afterwards. If this is his [Barnes's] last book, he has given his career a triumphant ending.” —Financial Times

”Disparate elements are bound together by the skilful management of theme and tone. Departure(s) is at once confidently authoritative and tentatively questioning. Barnes assumes a personal relation with his readers, built on the kind of intimacy that cancer's company doesn't provide.” —Times Literary Supplement

>>Changing My Mind.

Attention: Writing on Life, Art, and The World by Anne Enright $40

Anne Enright has always been alert to the places where public and private meet, where individual lives are caught by, or alter, the sweep of history. These essays, collated from across Enright's career, take us from Dublin to Galway, Canada to Honduras, and through voices, bodies and time. They delve into Enright's own family history, and explore the free voices and controlled bodies of women in society and fiction. Enright has spent a lifetime reading as well as writing, and she offers new perspectives on writers including Alice Munro, Toni Morrison, James Joyce, Helen Garner and Angela Carter. Attention brings Anne Enright's wide-ranging cultural criticism, literary and autobiographical writing together for the first time. In Enright's fiction, speech can transform, rupture, enliven and liberate. [Paperback]

”With all its incisiveness, wit and brilliant sanity, Anne Enright's Attention provides a glorious antidote to the mad, sad world.” —Eimear McBride

”Anne Enright's essays are a joy to read: incisive, wise, often humorous, they are explorations of the way we live in the world today. I turned down so many page-corners as I read that I now cannot shut my copy of the book.” —Maggie O'Farrell

The Haunted Wood: A history of childhood reading by Sam Leith $30

Can you remember the first time you fell in love with a book? The stories we read as children matter. The best ones are indelible in our memories; reaching far beyond our childhoods, they are a window into our deepest hopes, joys and anxieties. They reveal our past — collective and individual, remembered and imagined — and invite us to dream up different futures. In a pioneering history of the children's literary canon, The Haunted Wood reveals the magic of childhood reading, from the ancient tales of Aesop, through the Victorian and Edwardian golden age to new classics. Excavating the complex lives of our most beloved writers, Sam Leith offers a humane portrait of a genre and celebrates the power of books to inspire and console entire generations. [Now in paperback]

”Sam Leith has been encyclopedic and forensic in this journey through children's books. It's a joy for anyone who cares or wonders why we have children's literature.” —Michael Rosen

”Scholarly but wholly accessible and written with such love, The Haunted Wood is an utter joy.” —Lucy Mangan

”One of the best surveys of children's literature I've read. It takes a particular sort of sensibility to look at children's literature with all the informed knowledge of a lifetime's reading of 'proper' books, and neither patronise (terribly good for a children's book) nor solemnly over-praise. Sam Leith hits the right spot again and again. The Haunted Wood is a marvel, and I hope it becomes a standard text for anyone interested in literature of any sort.” —Philip Pullman

Whāia te Taniwha: Kōrero from Te Waipounamu edited by Chloe Cull and Karuna Thurlow $30

Taniwha have shaped the land and navigated the waterways of Te Waipounamu for generations. They are shapeshifters, oceanic guides, leaders, ancestors, adversaries, guardians and tricksters who have left their marks on the land around us. Let the twelve Kāi Tahu artists and writers in this new book for rakatahi take you on a journey around the motu as we follow the tales of taniwha, both ancient and new. Weaving together te reo Māori and English, they explore how we can learn from taniwha — and what they can teach us about ourselves and our ever-changing world. Highlights: —A compelling introduction to taniwha for tamariki and rangatahi aged 8 to 15. —Stories located in Te Waipounamu South Island, by Kāi Tahu artists and writers. —Bilingual texts for te reo Māori speakers and learners alike, with a particular emphasis on te reo o Kāi Tahu. —Perfect for use by kaiako and ākonga in both English Medium and Māori Medium education contexts. Contributors: Justice-Manawanui Arahanga-Pryor, Leisa Aumua, Conor Clarke, Lucy Denham, A. J. Manaaki Hope, Meriana Johnsen, Moewai Rauputi Marsh, Waiariki Parata-Taiapa, Andrea Read, Jayda Janet Siyakurima, Ruby Solly, Paris Tainui. [Hardback]

>>Look inside.

Green Ink by Stephen May $40

David Lloyd George is at Chequers for the weekend with his mistress Frances Stevenson, fretting about the fact that his involvement in selling public honours is about to be revealed by one Victor Grayson. Victor is a bisexual hedonist and former firebrand socialist MP turned secret-service informant. Intent on rebuilding his profile as the leader of the revolutionary Left, he doesn't know exactly how much of a hornet's nest he's stirred up. Doesn't know that this is, in fact, his last day. No one really knows what happened to Victor Grayson — he vanished one night in late September 1920, having threatened to reveal all he knew about the prime minister's involvement in selling honours. Was he murdered by the British government? By enemies in the socialist movement (who he had betrayed in the war)? Did he fall in the Thames drunk? Did he vanish to save his own life, and become an antiques dealer in Kent? Whatever the truth, Green Ink imagines what might have been with brio, humour and humanity. [Hardback]

“May skilfully orchestrates a large cast of both historical and fictional characters. The novel's period detail is impeccable. One of its chief pleasures is the authorial voice, which, with its maxims on pity, ambition, boredom and so forth, is of an omniscience rarely encountered in contemporary fiction.” —Financial Times

”An idiosyncratic, rather dreamlike novel: it doesn't so much bring history to life as use a clutch of historical figures to showcase the author's own captivatingly offbeat intelligence.” —Jake Kerridge, The Telegraph

”A vivid and wholly credible recreation of post-Great War London. All is imagined here in convincing and sardonic — and frequently hilarious — detail.” —Robert Edric

”Stephen May is the spry, sardonic voice of the new historical fiction.” —Hilary Mantel

>>War, trauma, and politics.

>>A firebrand’s last day.

>>On Victor Grayson.

Gaza: The story of a genocide edited by Fatima Bhutto and Sonia Faleiro $30

"Genocide destroys cities and claims lives, but it also remakes the psyches of those it spares." The story of genocide belongs first to its survivors. In this urgent and powerful collection, Ahmed Alnaouq recounts the devastating loss of twenty-one family members. Noor Alyacoubi offers a searing account of starvation in Gaza. Mariam Barghouti examines the brutality of Israeli settler violence in the West Bank, while Lina Mounzer reports on the aftermath of Israel's simultaneous bombing of Lebanon. Their testimonies, along with those of many others, illuminate the enduring psychological and physical toll of state violence. Gaza: The Story of a Genocide brings together personal testimony, expert analysis, poetry, photography, and frontline reportage to document the full scope of destruction inflicted on the indigenous Palestinian people — their lives, their land, and their future. With illustrations by Joe Sacco and Mona Chalabi, it includes the work of the late poet Hiba Abu Nada, who was killed by an Israeli airstrike on her home in Khan Younis, Gaza, on October 20, 2023. Other contributors include Mosab Abu Toha, Susan Abulhawa, Laila Al-Arian, Tareq Baconi, Eman Basher, Omar Barghouti, Yara Eid, Huda J. Fakhreddine, Dr. Tanya Haj-Hassan, Yara Hawari, Maryam Iqbal, Nina Lakhani, Ahmed Masoud, Lina Mounzer, Malaka Shwaikh, Shareef Sarhan, and Mary Turfah. [Paperback]

Hate: The uses of a powerful emotion by Şeyda Kurt $37

Hatred is typically characterised as ugly, destructive and, above all, the political tool and dominant emotion of intransigent right-wingers. But is something important lost in this simplistic depiction? Don't those engaged in anticolonial, feminist, or class struggles — the very people who, in mainstream narratives, are usually portrayed as victims and objects of hate — have just reasons for feeling hatred? Şeyda Kurt, who approaches the topic from both personal and historical angles, challenges the consensual liberal perspective, reframing the exploited and oppressed as vehicles as well as targets of hatred. She weaves together the stories of Jewish avengers resisting German fascism, the Haitian revolutionaries, contemporary abolitionists, and many others, ultimately arriving at the revolution in Syrian Kurdistan and the question of a just peace. Kurt argues that the pursuit of justice is sometimes spurred by destructive impulses and hostility. What happens then to the tenderness we share as human beings? When we allow ourselves to hate, what becomes of the kindness we would bestow upon a world we are striving to protect? Kurt examines strategic hatred as a powerful force driving resistance, abolition, and even, paradoxically perhaps, radical care. [Hardback]

”A brilliant meditation on the relationships between hate, domination, and resistance. Kurt shows how the concept of hate is deployed to stigmatize and discredit anti-colonial, anti-racist, and feminist resistance, and how liberal moral stances against hate operate to pacify and to justify state violence through appeals to democracy and rule of law. This book is a vital tool for demystifying hate, so that we might see its role in liberation struggles.” —Dean Spade

>>Is hate politically useful?

The Hill in the Dark Grove by Liam Higginson $38

Carwyn and Rhian — the last in a long family line of sheep farmers — are living out a brutal year in their hillside farm, deep in the mountains of Eryri, North Wales. When Carwyn stumbles across a stone circle and some sort of burial mound in one of the fields on their land, he quickly develops an obsession. His wife, Rhian, meanwhile, is confronted with the growing realization that the man with whom she shares her life and home is slowly becoming a frightening stranger. As the harsh mountain winter closes in, Rhian finds herself alone with her increasingly peculiar husband, the mountains, and the looming megalithic stones. The Hill in the Dark Grove is a story of a lost way of life and the lengths we go to to protect what we know. [Paperback]

”Witty, tender, ultimately terrifying. Evocative and deftly done; The Hill in the Dark Grove is a book of echoes, haunted by the sheer vastness of time and landscape, and how they enact upon us and the stories we tell. A celebration of love's persistence, a summoning of ancient lore, a superb debut.” —Kiran Millwood Hargrave

”Liam Higginson is a new talent in Welsh storytelling; atmospheric, chilling and incredibly touching, The Hill in the Dark Grove holds the reader in its arms, and shows us how our stories, our objects and memories, are shaped and held by the land.” —Joshua Jones

”The Hill in the Dark Grove is a sumptuously written, dark meditation on aging, obsolescence, and the brutalising march of time and progress, as well as a chilling folk horror novel. There's something long buried in the mountains of North Wales and within the sheep herders, Carwyn and Rhian, who are economically pushed beyond their limits; Liam Higginson expertly brings it all to the surface.” —Paul Tremblay

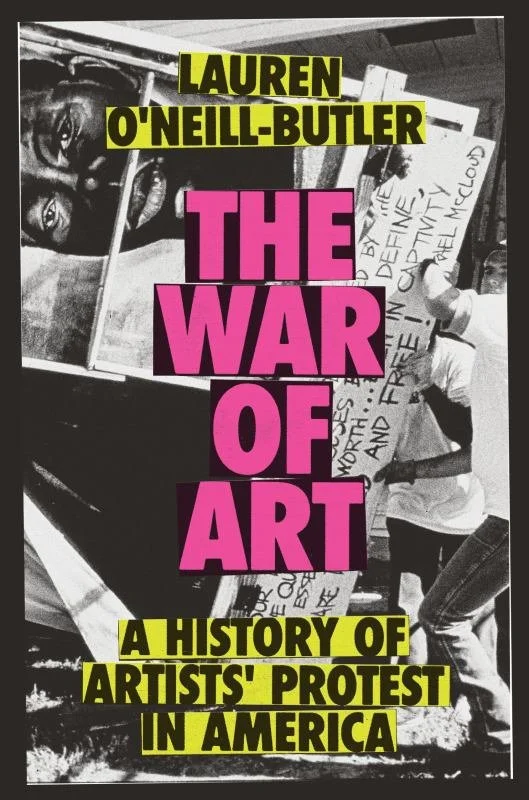

The War of Art: A history of artists’ protest in America by Lauren O’Neill-Butler $45

Artists in America have long battled against injustices, believing that art can in fact "do more." The War of Art tells this history of artist-led activism and the global political and aesthetic debates of the 1960s to the present. In contrast to the financialized art market and celebrity artists, the book explores the power of collective effort - from protesting to philanthropy, and from wheat pasting to planting a field of wheat. Lauren O'Neill-Butler charts the post-war development of artists' protest and connects these struggles to a long tradition of feminism and civil rights activism. The book offers portraits of the key individuals and groups of artists who have campaigned for solidarity, housing, LGBTQ+, HIV/AIDS awareness, and against Indigenous injustice and the exclusion of women in the art world. This includes: the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), David Wojnarowicz's work with ACT UP, Top Value Television (TVTV), Agnes Denes, Edgar Heap of Birds, Dyke Action Machine! (DAM!), fierce pussy, Project Row Houses, and Nan Goldin's Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN). Based upon in-depth oral histories with the key figures in these movements, and illustrated throughout, The War of Art is an essential corrective to the idea that art history excludes politics. [Hardback]

”A wonderfully smart, readable and informative study of a topic that matters to almost everyone interested in art, which is more than enough to recommend it. But gems like the luminous chapter on Agnes Denes and the eye-opening revisionary discussion of her relation to Smithson make it something even better. Essential reading.” —Walter Benn Michaels

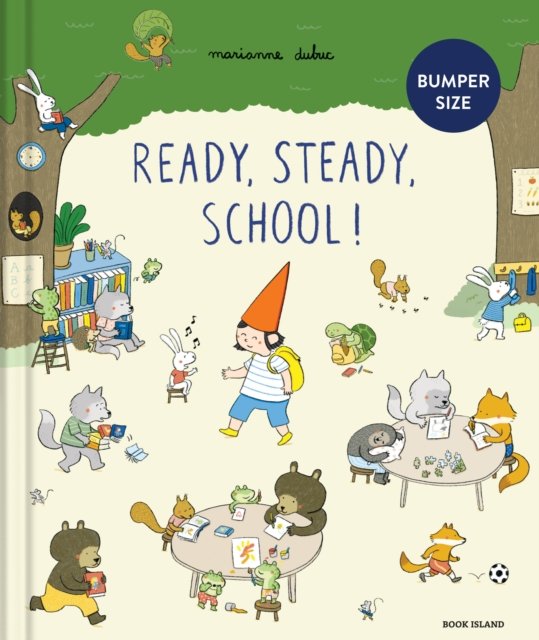

Ready, Steady, School! by Marianne Dubuc $48

A wonderful large-format search-and-find book. Next year, Pom will be starting school. But a year's too long to wait when you're excited. Today, Pom has decided to visit some friends by dropping in on different animal schools. At Little Leapers, the rabbits are learning how to read, write and count. At Bulrushes, the frogs are creating beautiful artwork. At F is for Foxtrot, the foxes are playing different sports.. What if Pom's dream school was a little bit of all that? One thing's for sure: school is an amazing adventure! This book is perfect for those keen to start school and for those who might need a little reassurance. [Hardback]

>>Look inside!

Read our 465th newsletter

23 January 2026

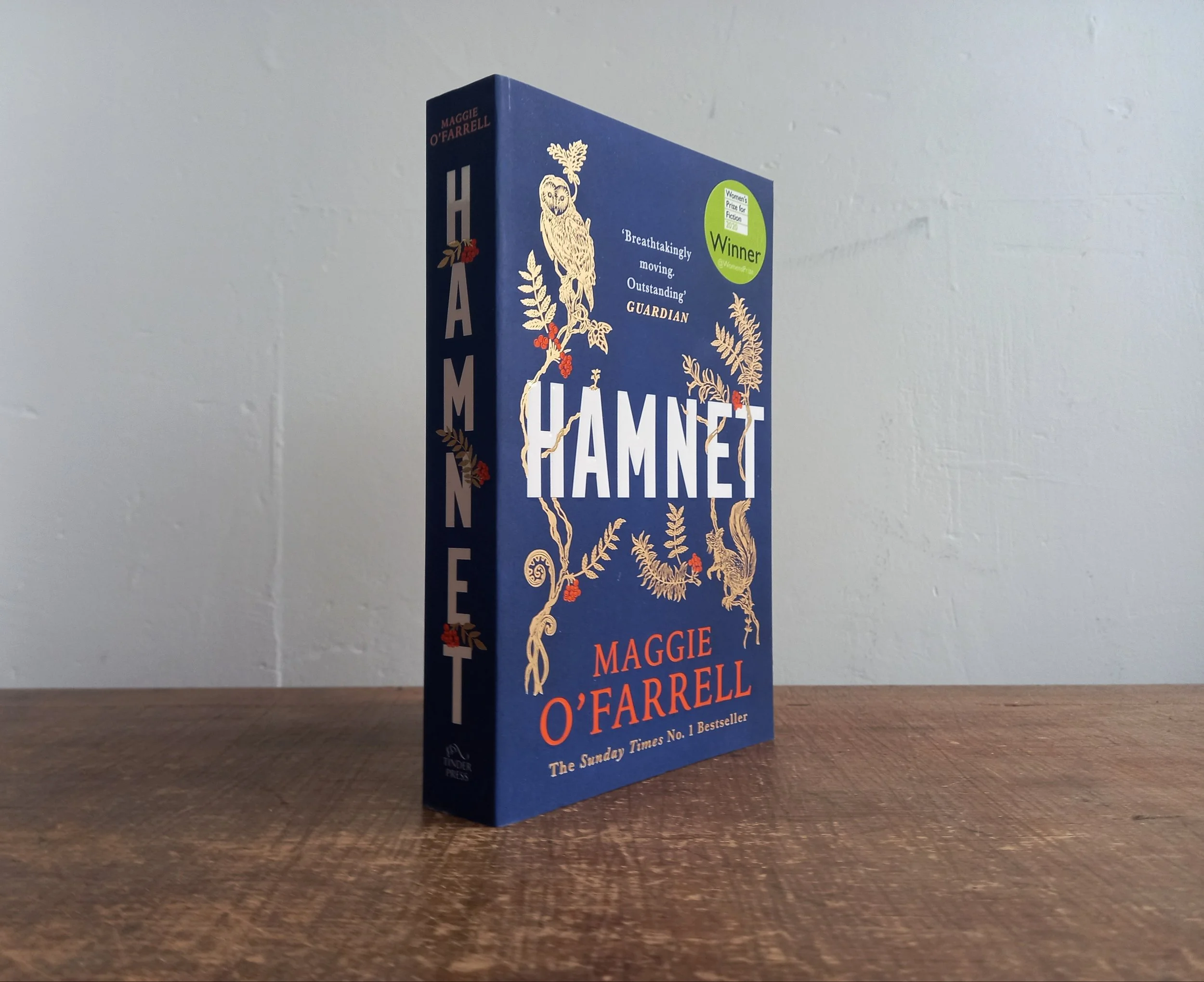

This evocative, heart-breaking, and revealing story of grief lays bare the genesis of Shakespeare’s most famous play, Hamlet. Yet in Maggie O’Farrell’s novel, Hamnet, Shakespeare as we know him hardly has a role. Set almost exclusively in the village of Stratford-upon-Avon and centred around the domestic life of his wife and family, Will is referred to as the Latin tutor, the glover’s son, the father, the husband. and is often working away — letters arriving at intervals. Who do we meet on the first pages, but the son — desperately searching for an adult to help him. His sister is unwell and the plague is present. From here, as time and the shadow of death make their presence known, we circle back increment by increment into the world of this child and his sister, of the mother, of the extended family and the village. We circle further back to the young Latin tutor gazing out the window, bored by the tedium of his job with boys who will never become any great things, and spying a youth (at first he mistakes his future wife for a lad) with a bird (later we meet this kestrel) upon her arm; and circle back again to the reasons why he is entrenched in this wearisome role — his violent and domineering father. Agnes is central and crucial in this novel. O’Farrell takes what little knowledge of Shakespeare's wife and brings her to the reader as a full and fascinating woman in her own right. She reels from the pages with her supposed eccentricities — she is a gifted healer, a lover of plants and the wilderness (seen by some in the community as a wild thing — a woman shunned by some but needed by others) — and her independent life. Emotional and emotive, sly and quiet, when death visits at her door, her grief is unbounded. Life has been snatched from her in a startling and, to her, an uncomprehending way. Agnes and Hamnet hold you in the grooves of this novel, make you want more, and they will stay with you long after the covers are closed. You reside within Hamnet’s mind as he navigates his twin sister’s illness, as he tries to find sense in the madness of the fever and the adult world that stands just outside his grip. You walk alongside Agnes as she loses herself in nature’s wildness to emerge into a world that can only tear at her, yet is necessary for survival and the memories that bind her child to her. Each character offers up a story — a way of seeing this world and telling its tale — a tragedy wrapped in intrigue on a small stage with rippling emotions. Hamnet is historical fiction at its best — in the vain of Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell series — it sets you fair and square in this time with all its life, death and drama. Immersive, compelling and rich in language and tale.

Perhaps the objects that carry the most meaning in our lives, the ones that are most imbued with the connections we have with the significant people in our pasts, the ones that both store and release the memories that are fundamental to our idea of ourselves, are not so much the precious heirlooms or heritage pieces but rather the ordinary objects that we use every day, just as, perhaps, their previous owners used them every day before us. The kitchen probably holds the greatest concentration of such useful-and-meaningful objects, come to us in many different ways, each with its own story. Bee Wilson’s thoughtful and beautifully written book tells the stories attached to 35 kitchen objects of many origins, and gives insight into the texture of the lives of the people who used them, and their importance to the people who use them now.

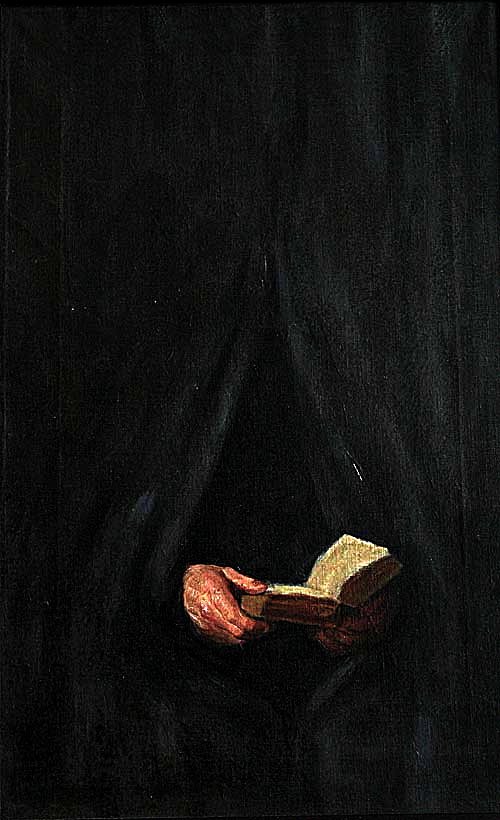

The hands holding the book in the painting by Markus Schinwald, and the black curtains between which they protrude, are painted in such a way as to make the viewer suspect that they are looking at a painting, or a part of a painting, by some Old Master, and the viewer, upon researching further, feels a little cheated to find that the artist is still alive. Had we perhaps confused even the name Markus Schinwald with that of some minor Germanic Old Master — perhaps a painter of agonising crucifixions, memento mori and surgically accurate Sts. Sebastians — which would have given this painting, in which the person holding the book into the light is effectively bodiless, concealed behind curtains, a disconcertingly suppressed reference to physical suffering? Maybe we should not feel cheated. Maybe it is the reference to the reference, by way of our confusion, that gives the painting, for us, its meaning.

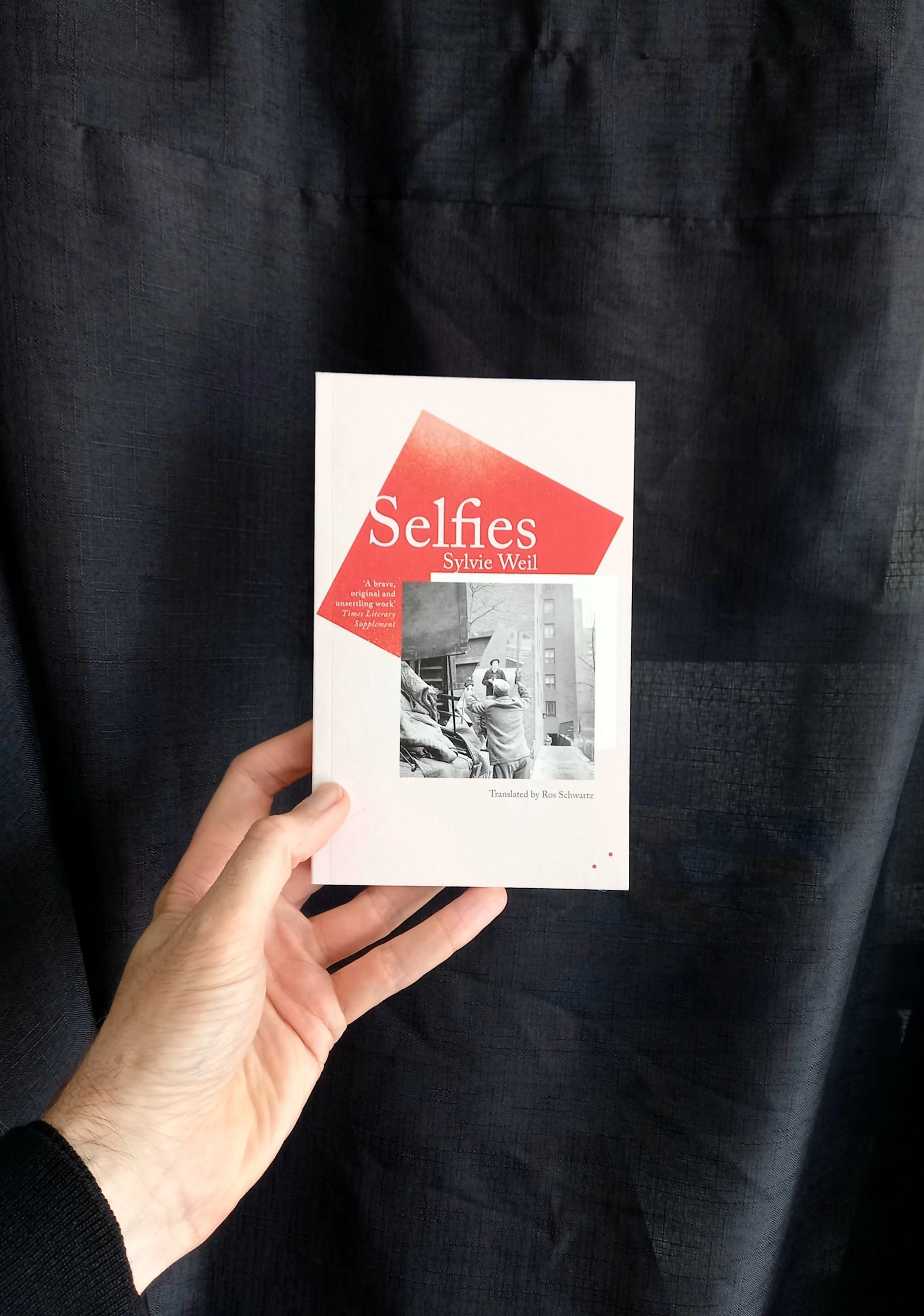

In the picture I didn't end up taking of myself I am sitting in an elderly armchair, the pile of its plush worn to the ghost of its original pattern on the arms and upper back. Beside me is a rather spindly green table upon which sits a vase of lilies, somewhat past their best, and a small empty coffee cup, a lip-mark of coffee at its rim. The sideboard behind me is stacked with books, and the fading light falls from my right onto the book I hold at an odd angle as if trying to postpone the moment in which I will have to get up and switch on a light. I am wearing something black and nondescript, seemingly a skivvy of some sort, liberally decorated with white cat hairs, and my head is thrust awkwardly forward over the oddly angled book, which I seem to be on the verge of finishing. Its title can be read despite the shadow: Selfies by Sylvie Weil.

*

The thirteen exquisite pieces of memoir that comprise Selfies each begin with a description of an actual artwork, a self-portrait by a woman ranging from the thirteenth century to today. This ekphrasis is followed by a description of a (possibly hypothetical) self-portrait by Weil which echoes or resonates with the historical work and provides a means of access to the third section of each piece, a more (but variously) lengthy examination of one of the more significant or uncomfortable aspects of Weil’s life. This tripartite structure demonstrates how viewing art can unlock new levels of understanding of our own lives, and how the communication of a stranger’s moment by means of a surface invariably stimulates the viewer’s memory to read that moment in terms of moments from the viewer’s own life, moments pressing at the surface of consciousness from the other side, so to speak. Viewing is remembering. The rigour and delicacy Weil demonstrates in viewing the artists’ works allows her to apply a similar set of criteria to her own memory-images, resulting in a remarkably nuanced set of realisations to be accessed and conveyed, potentially provoking a similar deepening of access in a reader to their his own memories. Weil’s prose, pellucidly translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, gauges subtle shifts of tone, frequently shifting our understanding of situations or persons before any knowledge about them is attained. The awful American mathematician with whom Weil had a love affair, her son’s mother-in-law, the close friend of her mother’s, the unsympathetic owners of a “Jewish” dog, are all revealed as having complex and often ambiguous relationships with the surfaces they present. Weil’s sentences, at once so straight-forward and so subtle, can move both outwards and inwards at once, operating at various depths simultaneously, as when Weil describes responses to her adult son’s mental breakdown: “I reply politely to friends who say: ‘I wouldn’t be able to cope if something like that happened to my son.’ I didn’t tell them that it could happen to anyone. And that they would cope, as people do. They’d have no choice. I don’t reply that they deserve to have it happen to them. Deep down, I agree that it is unlikely to happen to them. Not to them.” Precision often leads us to the verge of humour, as when Weil describes “the remains of a smile abruptly cut short, as if by the sudden and unexpected arrival of a dangerous animal.” The ‘Self-portrait as an author,’ springing from a description of a 1632 self-portrait of Judith Leyster seen as an advertisement for her portrait commissions (a commercial imperative), is a devastatingly perfect, almost Cuskian account of the people who visited Weil’s signing table at a literary festival. The book is full of images, or moments, details, that implant themselves in the mind of the reader and continue to resonate there in a way similar to the reader’s own memories. What is the purpose of self-depiction? “Everyone takes selfies,” Weil observes. “It’s a way of going unnoticed,” but at the same time each selfie is a form of searching, an attempt to locate oneself, somehow, in the circumstances that comprise one’s life. Memory is the only way we have to attempt to make sense of these moments.

This book begins with the question that prompted its author to stop writing for fourteen years: “Must I write?” In finally finding himself capable of addressing this question, Murnane also addresses its corollary: “Why had I written?" What follows is a subtle and often profound examination of the relationship between the ‘actual’ world and the image world from which fiction arises. Inverting the traditional Romantic model of fiction, Murnane disavows the so-called ‘imagination’ and instead stakes out the primary territory of his image world: “what I call for convenience patterns of images, in a place that I call for convenience my mind, wherever it may lie or whatever else it may be a part of”. By emphasising the porosity of a work of fiction, which is “capable of devising a territory more extensive and more detailed by far than the work itself”, Murnane shows that although the territory is landmarked by images introduced from the memory of events or fictions or artworks or other experiences, both author and reader inhabit the spaces between and surrounding these landmarks, find themselves exploring and enlarging the backgrounds of pictures and the spaces surrounding texts, and forming relationships with ‘personages’ who are both part of, and give rise to, the personages of both author and reader. Every region written about implies a further region not yet written about, “a country on the far side of fiction”, inhabited by personages who may be accessible to the personages in fiction but not yet to us. In tracing (and correlating) the memories of the personage of the narrator-Murnane and the memories of the main character in the book he abandoned when he stopped writing, Murnane gives an exacting topography of his mind (“so to call it”) and a precisely worded description of its operations, and of the yearning, distance and loneliness that both underlie and seek remedy in fiction.

All your choices are good! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

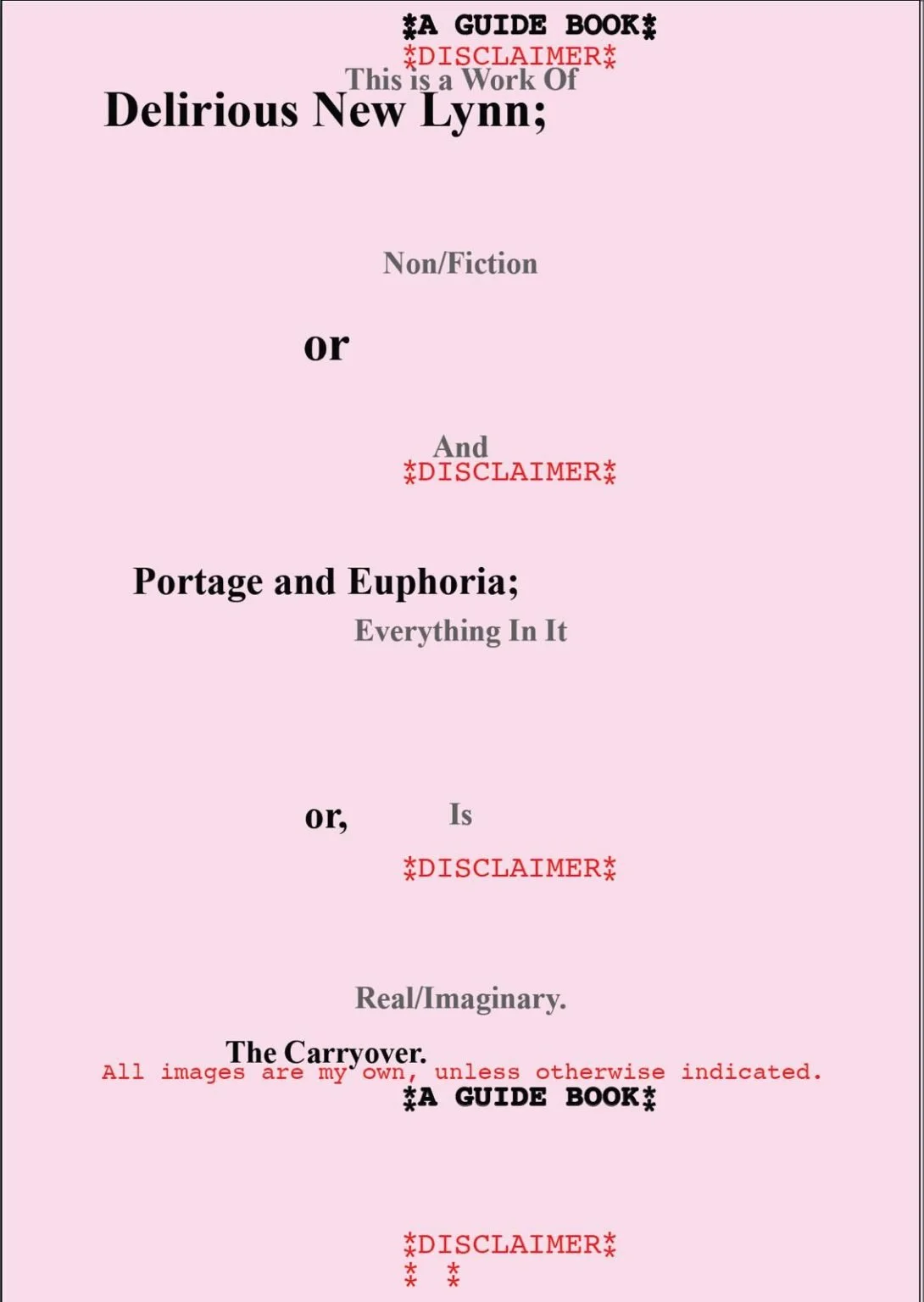

Delirious New Lynn, or, Portage and Euphoria, or, The Carryover: A guidebook by Oscar Mardell $35

Delirious New Lynn is the record of an obsession with an unnavigable backwater, a voracious drift down various culs-de-sac, an anti-psychogeography, a map of the schisms between mind and place, a poetics of trash, a rummage through the wastelands of Neoliberalism, a scavenger-hunt for meaning and nothingness, coincidence and randomness, beauty and ugliness, comedy and tragedy, comfort and horror, magnificence and absurdity, and spirituality too. Above all, it is a profusion of lists and digressions. This new book from the author of Great Works will have you in intellectual stitches as it snidely nails the Auckland suburb (and so much else about life in these times and on these shores). [Paperback]

>>Read an extract.

>>Look inside.

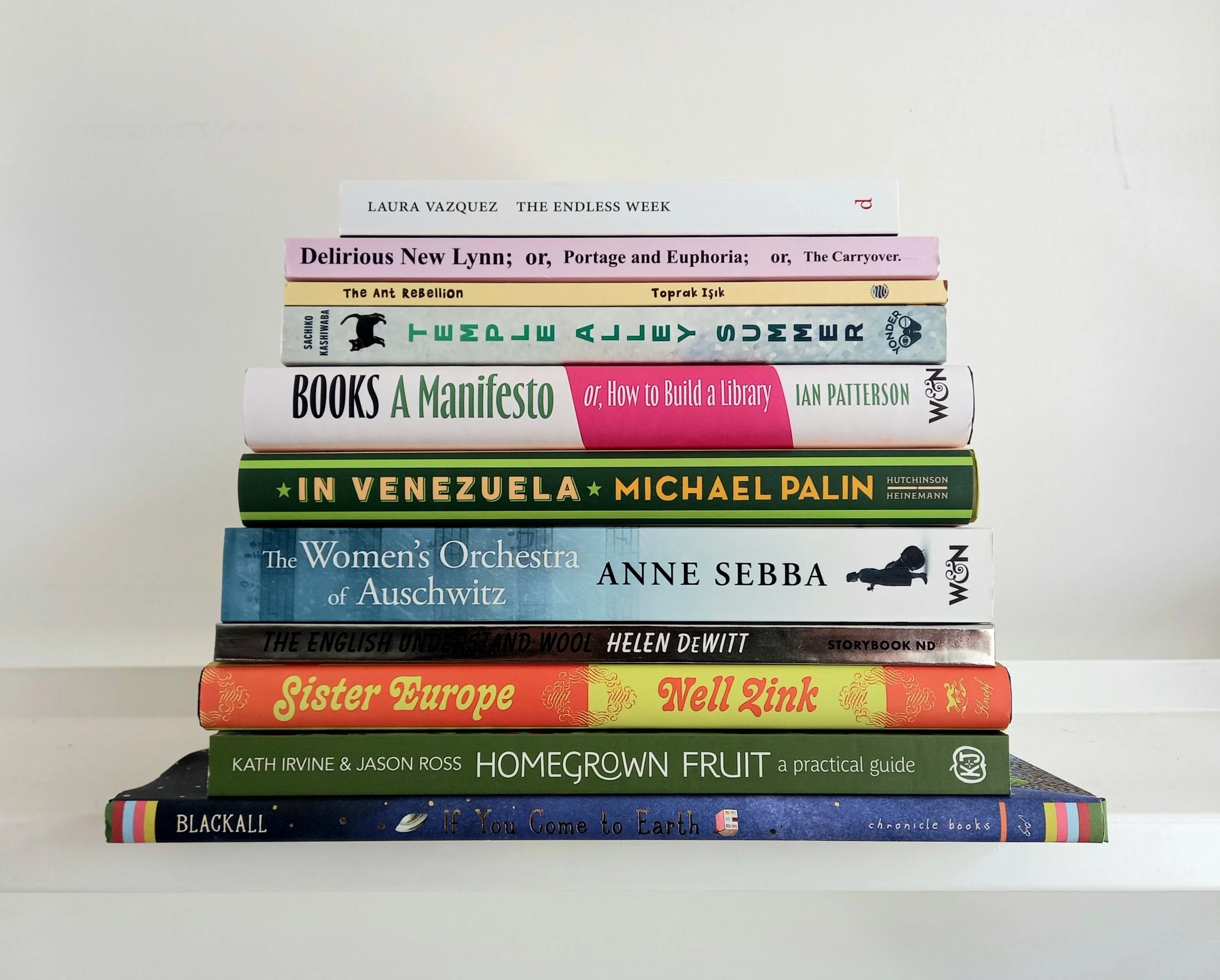

The Endless Week by Laura Vazquez (translated from French by Alex Niemi) $48

Like Beckett's novels or Kafka's stranger tales, The Endless Week is a work outside of time, as if novels had never existed and Laura Vazquez has suddenly invented them. And yet it could not be more contemporary, as startling and constantly new as the scrolling hyper-mediated reality it chronicles. Its characters are Salim, a young poet, and his sister Sara, who rarely leave home except virtually; their father, who is falling apart; and their grandmother, who is dying. To save their grandmother, Salim and Sara set out in search of their long-lost mother, accompanied by Salim's online friend Jonathan, though their real quest is through the landscape of language and suffering that saturates both the real world and the virtual. The Endless Week is sharp and ever-shifting, at turns hilarious, tender, satirical, and terrifying. Not much happens, yet every moment is compulsively engaging. [Paperback]

"Reading this book feels like falling into a whirlpool: it's inescapable." —Maggie Lange, W Magazine

"Vazquez has created a unique and enduring novel. Something hard and real and tangible glitters amid the vapour of text and image she describes." —Dustin Illingworth, New Left Review

"Are the kids ok? Are the elders? Are the gods? Are the dead? In this mesmeric novel, loneliness and the (online) community, language and image, the immediate and the mediated, violence and care construct a tender, precarious microzone called intimacy. A lumbar puncture of a book, a golden strain." —Joyelle McSweeney

"It's a rigorously unsettling reading experience, without plot, tension, or character development. But the details and countless vignettes deliver an immense range of emotion. Grotesquely inventive and amusing, like a corner torn from a Hieronymus Bosch painting." —Kirkus

"They say a truly great author can write about anything and make it interesting, and with The Endless Week Laura Vazquez proves that true on every page. If you're in search of an ultra-contemporary novel that shatters all the rules with inimitable humor and style to spare, look no further — she's arrived." —Blake Butler

>>Inside out experience.

Sister Europe by Nell Zink $65

As a Berlin night draws in around the pristine glass exterior of the Hotel Interconti, a ragtag group of friends, family, and potential lovers find themselves frustrated. By promise or threat, they have all gathered at a lavish celebration of an elderly author's venerable career. But dinner is delayed, the speeches are a drag and the gang — a young trans teen and her father; an ageing publisher and his flakey date; a dog, a troubled heiress and an Arab Prince — begin to feel the pinch of boredom, hunger and horniness. Together they will make their bid for freedom, and will soon embark on an exhilarating odyssey through the city's shadow and light. Sophisticated, sexy and exquisitely funny, Sister Europe is the remarkable new novel from one of the most singular, brilliant writers working today: a vivid tale of growing up, growing old and getting down. [Hardback]

"To stay out late in Zink's world, loitering, is a pleasure. Her voice is cool and fastidious, but she has a screwball quality-a comic sensibility rooted in pain. She grinds her own sophisticated colors as a writer; her ironies are finely tuned; she is uniquely alert to the absurdities of human conduct." —Dwight Garner, The New York Times Book Review

"This sly, sprightly novel provides a distraction from the news while the news is all over it. One of the pleasures of Sister Europe is that it's thoroughly up-to-date but still shaped in the timeless way of Wodehousian comedy of errors." —Sam Sacks, The Wall Street Journal

"Zink is one of the most humane writers we've got, and one of the best. As ever, Zink is funny in a way that requires careful observation and precision. The night narrated here feels like the kind of time outside of time in which classical comedies take place — a liminal space in which characters experience transformations impossible in the everyday world. Here, some characters find each other, some find their way home, and some get a bit closer to finding themselves." —Kirkus Review

”Nell Zink is a writer of extraordinary talent and range. Her work insistently raises the possibility that the world is larger and stranger than the world you think you know.” —Jonathan Franzen

”Zink writes with a joyful recklessness that makes her one of the freshest talents around.” —The Guardian

>>Not entirely sure.

>>Connecting the dots.

>>At the back.

>>Somehow connected.

Books: A manifesto, Or, How to build a library by Ian Patterson $50

This is a book about books, about the subversive power of reading and the strange, enduring magic of books as objects. Ever since childhood, books have been at the centre of Ian Patterson's life, as a poet, teacher, translator, bookseller, and collector. As he constructs the last of many libraries, he makes an impassioned case for the radical importance of reading in our lives — from Proust to Jilly Cooper, from golden-age detective novels to avant-garde poetry. Wise, irreverent and exhilaratingly wide-ranging, Books: A Manifesto reminds us that poems know things that we might not yet know ourselves, urges us to seek out the puzzles alive in the art of translation and celebrates the singular elasticity of the 'bookshop minute'. But even more than this, the book insists on reading not as a luxury but a necessary part of reality: we live within language, and when we think, it's with the tools that reading gives us. Our time of cultural and political crisis demands more than books — but without them, and without the breadth of knowledge, sense of history, awareness of alternatives and hope for the future they offer, things will not get better. At once a primer for enriching your own library and a manifesto for why that matters, this book is an invitation to a deeper, richer world of thought and feeling — and a reminder of just how much books matter. [Hardback]

”A bibliophile's autobiography, a supremely generous instruction in reading and collecting, a short history of antiquarian bookselling, a celebration of unserious pleasures and a polemic for the most serious ones — Books: A Manifesto is all of this and more. Of course Patterson hasn't read everything: he's reread it, bought and sold it a few times, might even have translated it, and has profound and genial thoughts.” —Brian Dillon

Temple Alley Summer by Sachiko Kashiwaba (translated from Japanese by Avery Fischer Udagawa), illustrated by Mihi Satake $23

Kazu knows something odd is going on when he sees a girl in a white kimono sneak out of his house in the middle of the night was he dreaming? Did he see a ghost? Things get even stranger when he shows up to school the next day to see the very same figure sitting in his classroom. No one else thinks it's weird, and, even though Kazu doesn't remember ever seeing her before, they all seem convinced that the ghost-girl Akari has been their friend for years! When Kazu's summer project to learn about Kimyo Temple draws the meddling attention of his mysterious neighbour Ms. Minakami and his secretive new classmate Akari, Kazu soon learns that not everything is as it seems in his hometown. Kazu discovers that Kimyo Temple is linked to a long forgotten legend about bringing the dead to life, which could explain Akari's sudden appearance is she a zombie or a ghost? Kazu and Akari join forces to find and protect the source of the temple's power. An unfinished story in a magazine from Akari's youth might just hold the key to keeping Akari in the world of the living, and it's up to them to find the story's ending and solve the mystery as the adults around them conspire to stop them from finding the truth. [Paperback]

”This imaginative tale, enchantingly written and charmingly illustrated by veteran Japanese creators for young people, has a timeless feel. Its captivating blend of humor and mystery is undergirded with real substance that will provoke deeper contemplation. Udagawa's translation naturally and seamlessly renders the text completely accessible to non-Japanese readers. An instant classic filled with supernatural intrigue and real-world friendship. This charming story is both a layered, profound reflection on living life with purpose and a funny, suspenseful book with all the hallmarks of classic middle-grade literature.” —Kirkus Reviews

The English Understand Wool by Helen DeWitt $36

”Maman was exigeante — there is no English word-and I had the benefit of her training. Others may not be so fortunate. If some other young girl, with two million dollars at stake, finds this of use I shall count myself justified.” Raised in Marrakech by a French mother and English father, a 17-year-old girl has learned above all to avoid mauvais ton ("bad taste" loses something in the translation). One should not ask servants to wait on one during Ramadan: they must have paid leave while one spends the holy month abroad. One must play the piano; if staying at Claridge's, one must regrettably install a Clavinova in the suite, so that the necessary hours of practice will not be inflicted on fellow guests. One should cultivate weavers of tweed in the Outer Hebrides but have the cloth made up in London; one should buy linen in Ireland but have it made up by a Thai seamstress in Paris (whose genius has been supported by purchase of suitable premises). All this and much more she has learned, governed by a parent of ferociously lofty standards. But at 17, during the annual Ramadan travels, she finds all assumptions overturned. Will she be able to fend for herself? Will the dictates of good taste suffice when she must deal, singlehanded, with the sharks of New York? A testament to the power of false friends. [Glazed hardback]

"A staggeringly intelligent examination into the nature of truth, love, respect, beauty and trust. This is that rare thing, or merle blanc, as maman might say: a perfect book. I've read it four times, which you can do between breakfast and lunch." —Nicola Shulman, The Times Literary Supplement

"This is a short, sharp sliver of a story-only 64 pages — but every single word is pitch perfect. Think of it as the literary equivalent of a shot of ice-cold vodka-Belvedere or Grey Goose only, of course." —Lucy Scholes, Prospect

"A wonderfully sideways take on the complex intersections between class, wealth and power — intersections that invariably favour those who have most of them already." -- Alex Clark, The Observer

"The English Understand Wool is Helen DeWitt's best and funniest book so far — quite a feat given the standards set by the rest of her work. Its pages are rife with wicked pleasures. It incites and rewards re-reading." —Heather Cass White, The Times Literary Supplement

If You Come to Earth by Sophie Blackall $45

Inspired by the thousands of children she has met in travels around the word for Save the Children and UNICEF, two-time Caldecott winner Sophie Blackall has crafted an ambitious yet child-accessible book of ... well ... everything. Simultaneously funny and touching, it is a call to each of us to take care of both the Earth and each other, and to celebrate the many way that people live their lives on earth. [Hardback]

>>Look inside!

The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz by Anne Sebba $40

In 1943, German SS officers in charge of Auschwitz-Birkenau ordered that an orchestra should be formed among the female prisoners. Almost fifty women and girls from eleven nations were drafted into a hurriedly assembled band that would play marching music to other inmates, forced labourers who left each morning and returned, exhausted and often broken, at the end of the day. While still living amid the most brutal and dehumanising of circumstances, they were also made to give weekly concerts for Nazi officers, and individual members were sometimes summoned to give solo performances of an officer's favourite piece of music. It was the only entirely female orchestra in any of the Nazi prison camps and, for almost all of the musicians chosen to take part, being in the orchestra was to save their lives. What role could music play in a death camp? What was the effect on those women who owed their survival to their participation in a Nazi propaganda project? And how did it feel to be forced to provide solace to the perpetrators of a genocide that claimed the lives of their family and friends? Sebba traces these tangled questions of deep moral complexity with sensitivity and care. From Alma Rose, the orchestra's main conductor, niece of Gustav Mahler and a formidable pre-war celebrity violinist, to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, its teenage cellist and last surviving member, Sebba draws on meticulous archival research and exclusive first-hand accounts to tell the full and astonishing story of the orchestra, its members and the response of other prisoners for the very first time. [Paperback]

The Ant Rebellion by Toprak Işık (translated from Turkish by Alvin Parmar), illustrated by Sedat Girgin $26

Ants are famous for their hard work, but some ants prefer exploiting others rather than doing it themselves. One day the warrior ants discover the nest of the farmer ants and set out to make the farmers their slaves — but they don’t count on the spirit of resistance from the farmers. The Ant Rebellion is a universal allegory about freedom, resistance and change, featuring memorable characters from the loving couple Honey and Glasswing to the hilarious beetle Loafer. [Paperback]

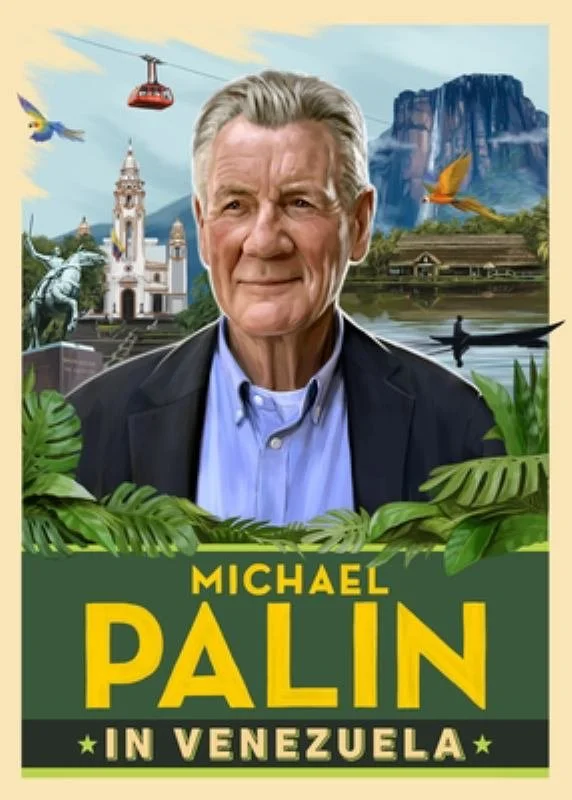

In Venezuela by Michael Palin $45

In February 2025, Michael Palin travelled to Venezuela to get a sense of what life is like in one of South America's most culturally rich, vibrant but also troubled nations. In the journal he kept during his trip he gives a vivid account of the towns and cities he visited, the landscapes he travelled through, and the people he met. Illustrated throughout with colour photographs taken on the trip, and permeated with his warmth and humour, this is a vivid and varied portrait of a complex country. [Hardback]

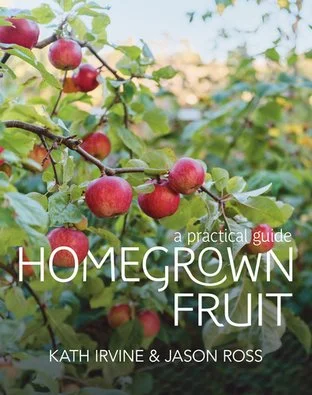

Homegrown Fruit: A practical guide by Kath Irvine and Jason Ross $58

Kath and Jason take you step by step to create a naturally, healthy orchard that thrives with minimal effort. You’ll learn how to choose the right varieties, plan a productive layout, build a living soil, assess tree health, and confidently prune, train, and care for your trees year-round. Real-world examples, sample plans and down-to-earth advice provide simple, practical solutions for gardens of every shape, size and climate. This inspiring, accessible book is perfect for beginners setting up a new orchard, busy people who want homegrown fruit without the fuss, and seasoned growers seeking deeper knowledge. Kath and Jason have over 25 years experience designing and managing home orchards in a diversity of environments across Aotearoa. The book's focus is on creating a healthy setup and choosing well-suited varieties. From this solid foundation fruit trees flourish, care is easy, there are a lot fewer pests and diseases and, most importantly, growing is fun! [Paperback]

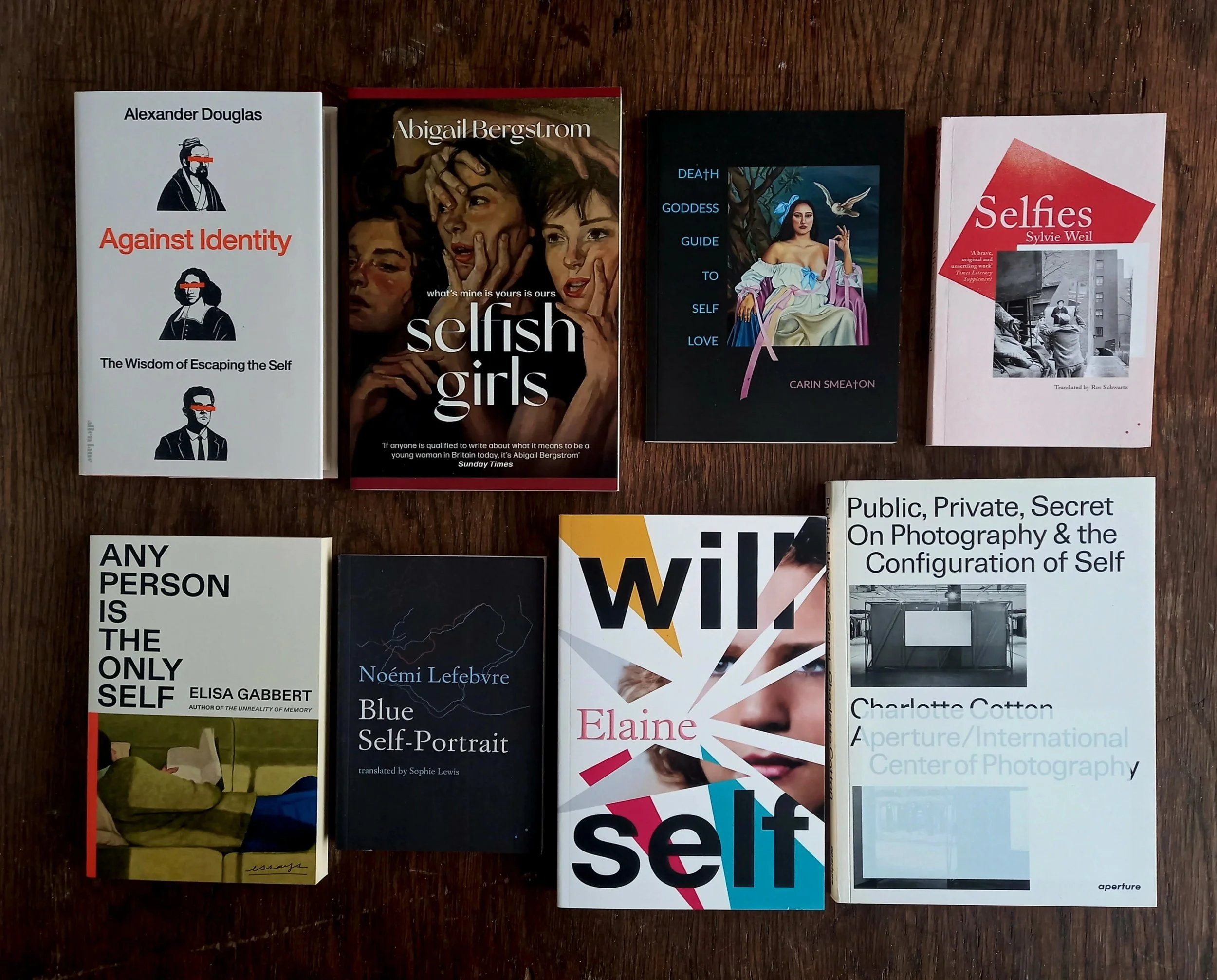

A Selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

Against Identity: The wisdom of escaping the self

Death Goddess Guide to Self Love

Public, Private, Secret: On photography and the configuration of the self

Read our 464th newsletter

16 January 2026

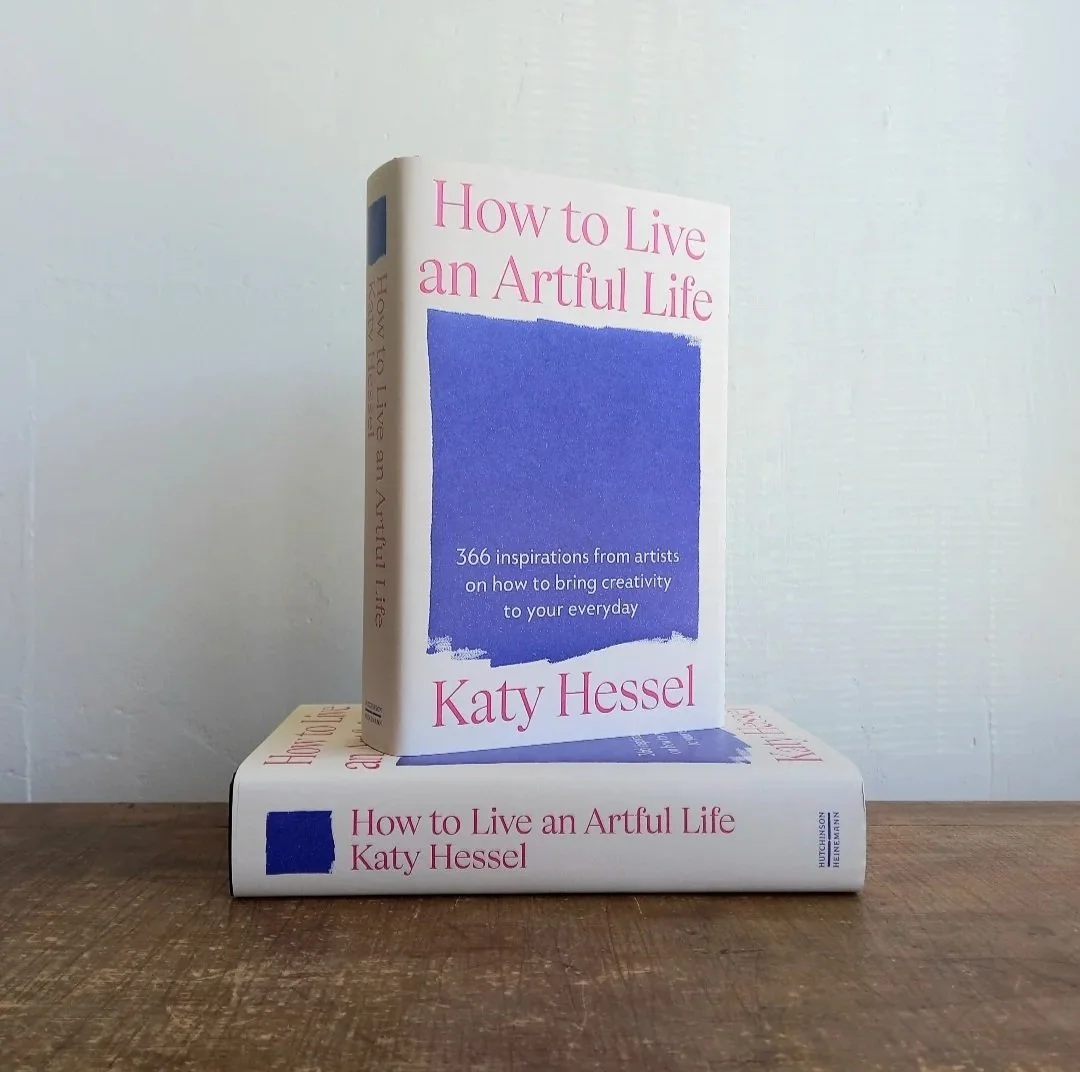

I’m usually suspicious of self-help books, inspiration-filled pages, and daily quotes, but when Katy Hessel’s book How to Live an Artful Life arrived, I was taken with it immediately. This may have been due my prior knowledge of her podcast, ‘The Great Women Artists’, or her art history book, The Story of Art Without Men, or because dipping in, I was intrigued by the breadth of the ideas, the quotes on creativity from both artists and writers, and the amount of information packed into each daily entry, and yes, inspiration. If you’re like me, and your art practice, although being an integral part of your psyche, is in practical terms an outlier crowded out by juggling two jobs, helping to keep the wheels turning at home, looking out for and spending time with your family, and the myriad of tasks that demand attention, then this is just the thing to enable a short window of focus. And this works for artists, writers, anyone that wishes to tune in to art (‘the artful life’) or learn to be more observant; to take the time. I’ll be using this book over the year ahead —366 entries, (but you can dip in and out wherever and whenever you like), so I’ve just read today’s entry. January 16: ‘Keep Looking’. It has a quote from writer Ruth Ozeki about spending time studying something intently — seeing more as you spend more time with an image or an object. This entry has a exercise to do. Some of the entries do — not all — but they are not compulsory, and by no means necessary, as the reading and your thinking will take you places. I’ve started a journal (I’ve always kept a visual diary (since being an art student), and occasionally blogged or had a journal on the go, but these have been erratic rather than systematic efforts) to go alongside the daily entries, jotting down my reactions to the passages and noteing ideas to come back to. (I’ve got 15 full pages already, so plenty of thoughts to record and ideas sparking!). The quotes from artists and writers are drawn from Hessel’s interviews or research, and it’s great to meet some new artists, as well as ones you know. So far, I’ve encountered Ali Smith, Ana Mendieta, Zoe Leonard, Louise Bourgeois, Tacita Dean, Deborah Levy, Kiki Smith, Anni Albers, plus 8 more. One a day. Their thoughts on creativity, Hessel’s commentary and things to think about or do, as well as information about the day’s artist or writer all packed into one succinct page or even half page. For the time-poor this is wonderful, as even on a busy day you can ensure at least keeping abreast of your reading, building a daily habit of engaging with and building your artful life. What I have found the most rewarding so far is remembering an artwork I hadn’t thought about in a long time, and the experience of interfacing with that work; looking at an object which I was very familiar with and finding something new in it; discovering some new artists and being reminded about ones that had slipped out of my consciousness; being more observant and remembering to push pause on the ongoing static of everyday menial tasks and open a window for a fresh portion of art. How to Live an Artful Life is both reassuring and challenging. Reassuring in the sense that your artful life hasn’t disappeared, it’s just a little overwhelmed by other demands and distractions; and challenging because you do find yourself stopping, questioning and focusing your mind on different ways to think about your relationship with art. Highly recommended.

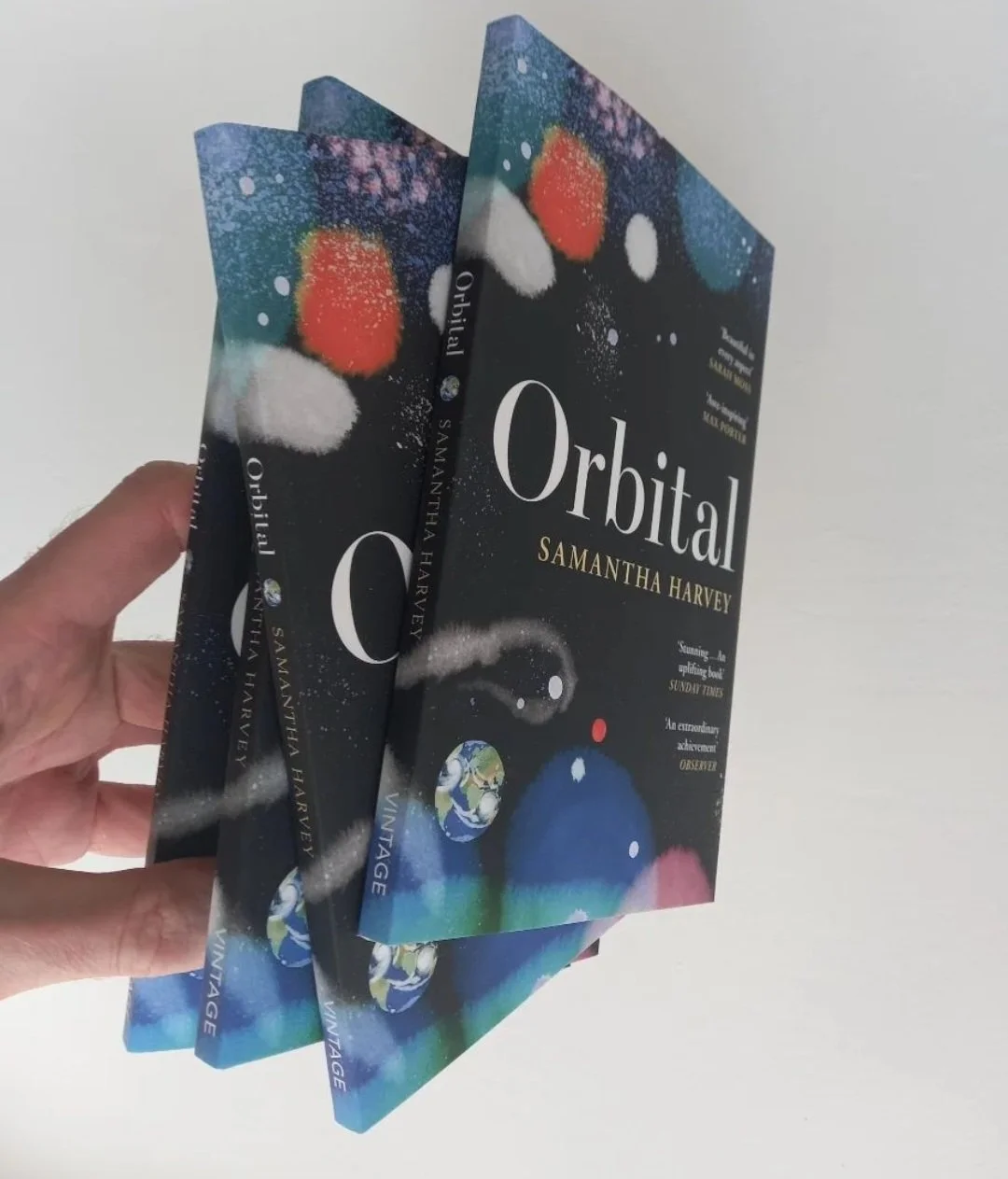

My life is a sort of an orbit, he thought. My life is a repetitive circular thing, or something very closely approximating a circle, not that an orbit needs to be circular, necessarily, but I think mine is. How many times will I pass this same point in the geography of my life, so to call it, how many times will I pass by, caught in the momentum of my orbit, unable to touch what I observe of my life below, changing slowly, or fast, as it does by the influence of various forces that I also cannot touch. But what am I if I am remote from what I have just called my life, he thought, what am I, the orbiting observer, if I am not my life, if I am orbiting above my life as the astronauts or cosmonauts in the space station in Samantha Harvey’s novel Orbital orbit above the planet Earth, orbiting and observing, enthralled by the attractive wonderful damaged planet below, remote from it but falling always towards it though never getting closer, in an equilibrium of gravity and momentum. An orbit, after all, he thought, is always firstly an act of attention. “Is it necessarily the case that the further you get from something the more perspective you have on it?” Harvey asks in the novel, as the astronauts stand in awe at the systems and patterns below them. “If you could get far enough away from Earth you’d be able finally to understand it.” Are understanding and participation mutually exclusive, he wondered, then, in my life, on this planet, necessarily, or is participation in itself a form of understanding, albeit enabled by an inescapable narrowing of perspective? As I circle in my orbit, far above my life, falling towards the object of my attention but carried away anyway by momentum, there in the equilibrium of my distance, I see there are no borders, no edges, no entities other than a oneness, if that could even be thought of as an entity, no entities other than those that exist in our minds, arbitrary borders, arbitrary edges, arbitrary entities, not seen from above but only by the participants in the struggle that they enable, the struggle that they condemn us to maintain. The moonshot is the opposite of an orbit. We divide ourselves with edges to get things done, to act one thing upon another, to intend and do, to participate or at least be aware of what we think of as our participation to the limited extent that we are somehow aware. This is how we get things done. This also is how harm is done. Up here in my orbit I observe how tiny all that is, I understand to the extent that I am remote, I am in a plotless place, I am in a place where everything is in an indefinite tense, where everything is a submission to a larger system, somewhere that I am hardly me. “As long as you stay in orbit you will be OK,” says the astronaut. “You will not feel crestfallen, not once.” I do not want to return, he thought. I do not want to leave my space of suspension, though “our hearts, so inflated with ecstasy at the spectacle of space, are at the same time withered by it.”

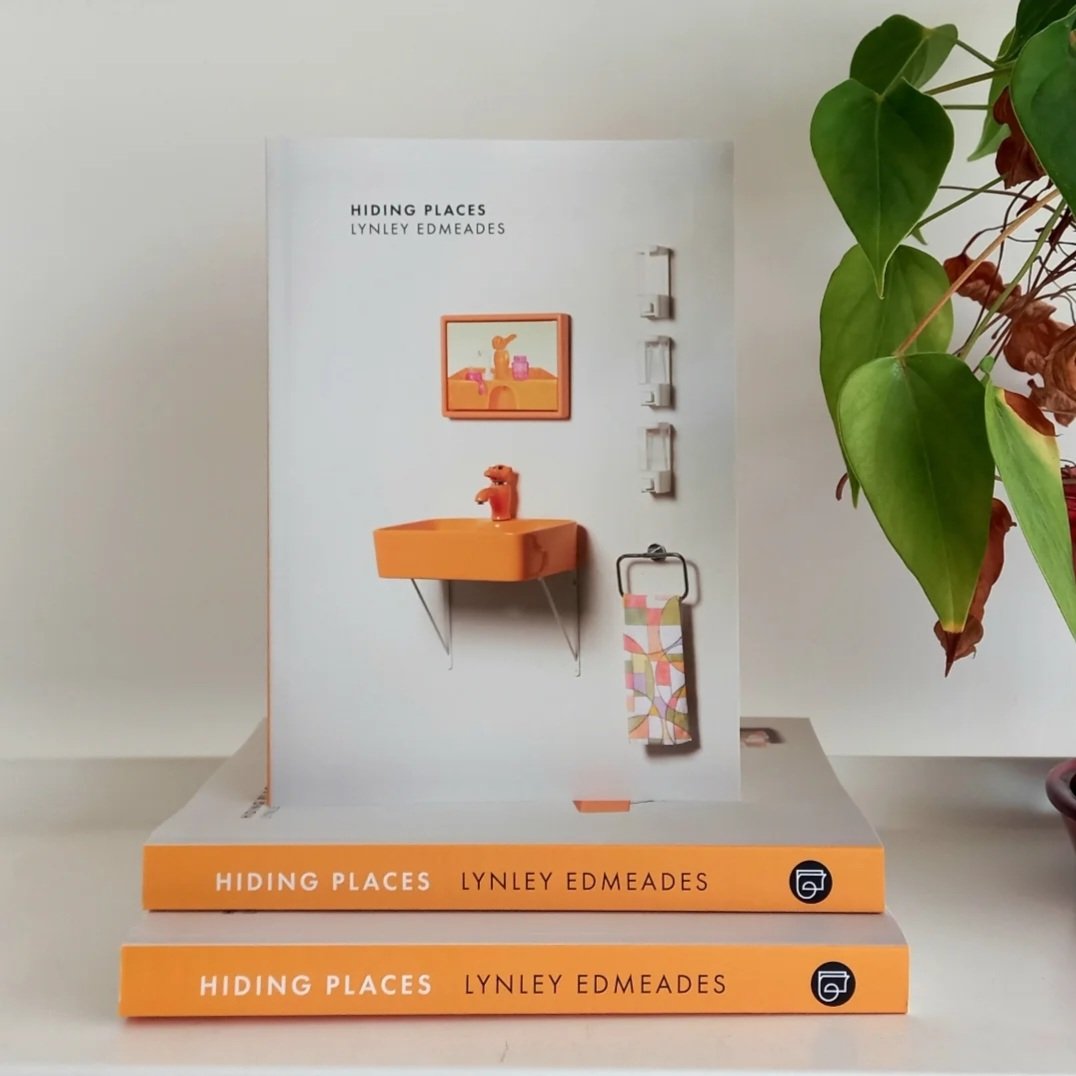

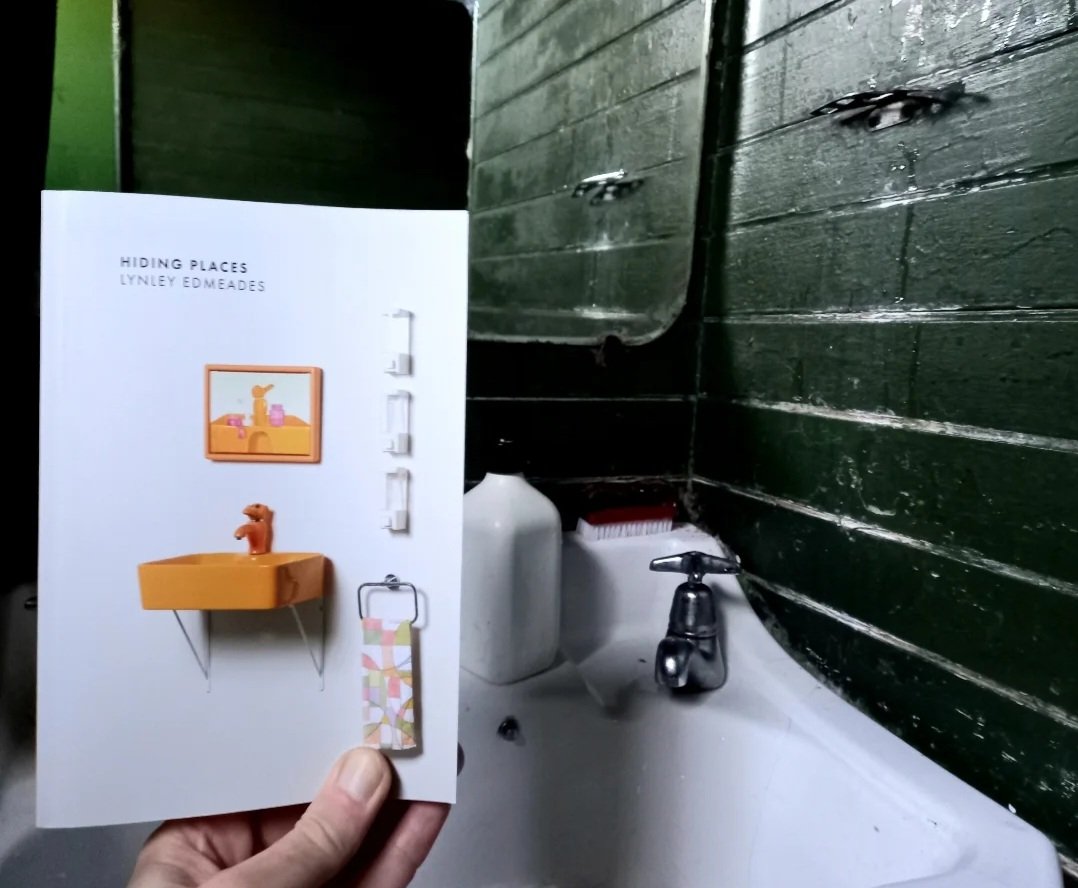

Lynley Edmeades’s Hiding Places is a book about the writing of a book (this book) in a life impacted by the arrival of a new life (a child) while caught also in a culture where both the writing of books and the raising of children are freighted with sets of judgements and expectations that make it hard to know, when you are doing either of these things best, if you are doing either of these things right (if there even is a right way of doing either of them). The fragmentary form of the book and the cumulative immediacy of the fragments, often slippery, often either pained or playful and frequently both, produce a work that is more confessionary than evasive while treasuring the possibilities of evasion, investigating shared experience while highlighting the irremediable particularity of the actual experiences it treats.

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

Read our first newsletter of the year!

Start your new year with a new book.

9 January 2026

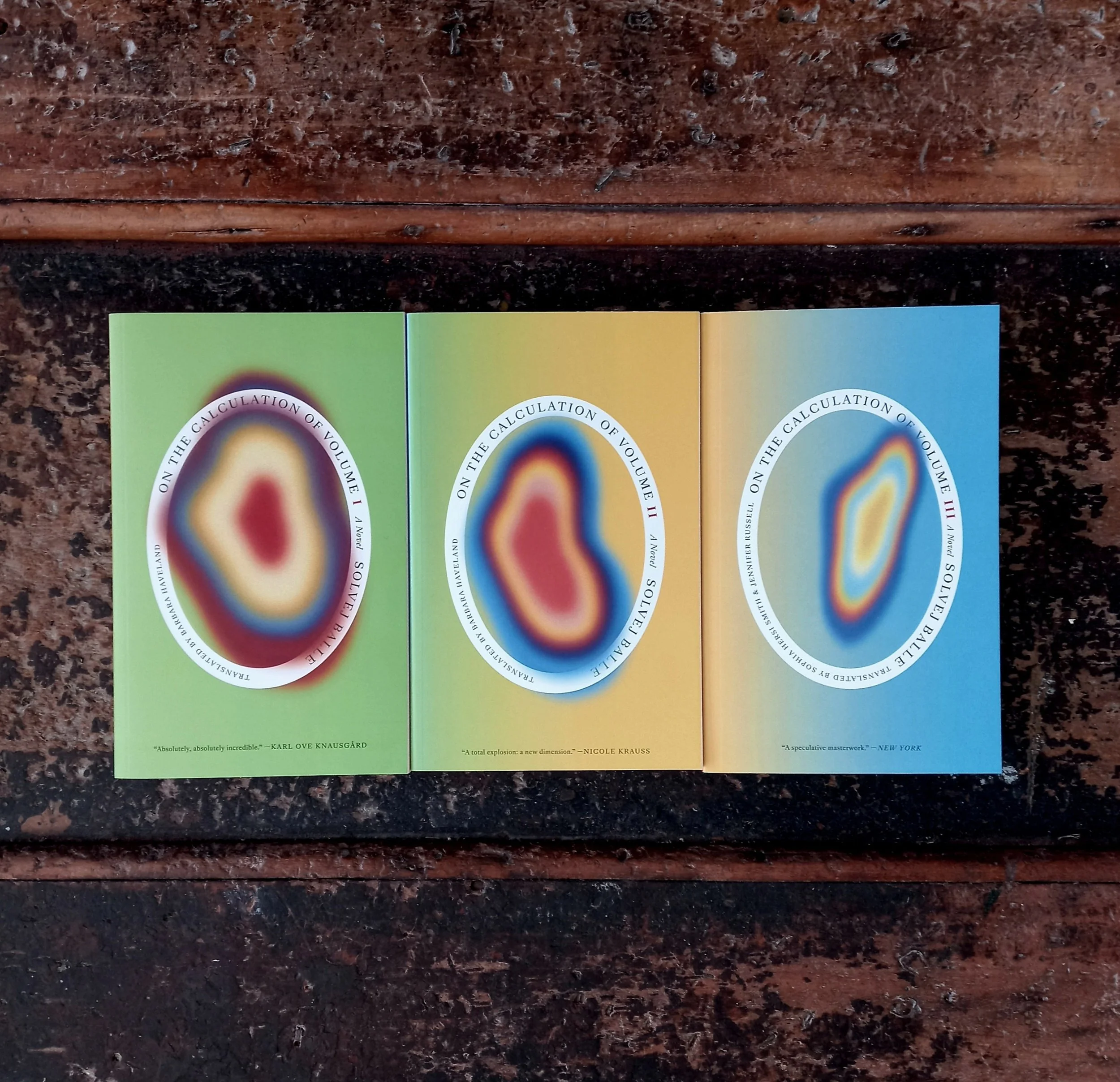

How can I write my review, or live my life, or do anything without repeating myself, I wonder. Here I go again! My life seems to consist of smaller and larger circles of repetition, my days are filled mostly of content indistinguishable from that which filled and will fill other days, barring some disaster or some miracle that is, though I have only my experience of this moment, shaded with what I call memory, inflected with what I think of as anticipation, to give me any idea of this repetition. I do experience repetition, I experience time, as if it actually exists, but how can I bear this? Any generalisation about the state of the world is a subjective state, but I suppose this endless repetition gets things done, I am a cog in the world-machine or else an untoothed wheel spinning needlessly and without traction, it is hard to tell, but I get things done. Repetition is the mode of action, but it causes me more suffering than it should. I think that perhaps I do not like getting things done. I think that I could so easily slip out of this shuddering machine, any thing could provide a way out, observing anything without the illusion of context would release me from its meaning and allow me to see it clearly, without language, without intention, without usefulness, but for what? Would this be the ultimate dislocation from my world or the ultimate dissolution in it? We repeat ourselves to keep the middle way, to preserve the idea that we have of ourselves, or the idea that others have of us. Tara Selter, in Solvej Balle’s seven-part novel On the Calculation of Volume, finds herself trapped in an endlessly repeating 18th of November, or she repeats her presence in what everyone else experiences as a single day. In this second volume, Tara decides to travel through Europe, guided by a meteorological chart, pursuing the experience of a passing year by moving to places where the conditions on the 18th of November resemble those she would associate with a changed season. She travels north to ‘winter’ and south to ‘summer’ and records the fiction of a passing year in a green notebook in a sustained attempt to live against the facts. When the notebook is stolen and does not reappear, Tara concludes, “I have had no seasons. Seasons are not scenes and locations. You cannot construct a year out of fragments of November.” She considers a Roman sestertius that she has with her and “At that moment I felt a void come into being. I felt a loss, a slide, a shift. It was as if a space was opening up, very slowly, not a big space, or at least it didn’t feel big, but I couldn’t close it again.” There is a ‘looseness’ to the world, she realises, and she is simultaneously immersed and separate from it. “I am walking around the streets, superfluous and out of circulation. It is not a disaster. It is not nothing, but it is not much either. Even the sound of my own feet is superfluous. I am walking through a space that ought to be empty. The place I occupy ought to be vacant, but for some inexplicable reason Tara Selter has taken it. I am in the way, I am a foreign body, an error. I am a strange creature who ought not to be among people with a direction.” It is solipsistic to consider myself an intruder on my own absence, as Tara does, but I suppose we are all intruders on our own absence (or absences (it is hard to know whether not existing is entirely a personal thing or something I would share with everything else that did not exist)). Everyone in this 18th of November experiences the day each time the same (there is no reiteration for them, after all), except when Tara intrudes upon their world and they are affected or respond to her. The anomalies she brings to them change their day but have no effect, for there is no day after, or if there is, Tara cannot reach it. What would be the cumulative effect of all these anomalies, the effects of Tara, if these became compound and consequential? She is right to consider herself a monster, after all. What Tara consumes is not renewed, so although it may seem that she is free from the consequences of her actions, the world, however out of joint, offers her no such liberation. Her dilemmas are those in which we all find ourselves all the time, though our lives are constructed in denial of them. We can follow no thought through to its end. We live against the facts in order to stay within the limits of the space where we can get things done. “My time is not a circle and it is not a line, it is not a wheel and it is not a river. It is a space, a room, a vessel, a container,” writes Tara. Each volume of this remarkable book provides a space for our thoughts, and equipment to stimulate its exercise.

Ever found yourself at a dinner party you would rather avoid? Zoe Dubno tackles art and the creative scene, New York-style, in this sharp, slightly nasty, often wickedly funny novel. Our narrator, after escaping the claustrophobia of an art-scene couple who love to collect young artists and writers, finds herself smack back in the centre of their world again after the overdose death of Rebecca, a highly strung actress and friend. Inside the head of our narrator, we view the scene from her position seated on the white sofa in the high-end designer city loft. Here, across the room from her is the couple: Eugene pouring himself another wine and pawing a young naive hopeful artist, and Nicole, now aging, but still projecting all that money, position, and confidence can bring, regal in her control of the room and the people in it. Here too, is The Writer, Alexander, for whom our narrator has a particularly nasty case of bile. The narrator, a writer of medium success and not a lot of confidence (hardly surprising considering the company she has kept) keeps us engaged with her wry asides, observant eye (especially in retrospect — she has escaped, although now is feeling a little trapped and somewhat contrite), and laugh-out-loud snarkiness. Yet you also, like her, are a little repulsed by the company. This tension is cleverly pulled at by Dubno — letting us see, making us laugh and curl our lip simultaneously. We observe, we have our narrator’s internal dialogue of disgust and also self-loathing to digest, as well as her shocking unguestlike behaviour — several times she can hardly contain herself, breaking into barking and inappropriate laughter. As you read on, her behaviour towards this circle of writers, artists, wannabes, and the maniapulative couple at its centre is fully warranted. Here they wait for the guest of honour, a famous actress, here they say shallow things about the recently deceased Rebecca, they pontificate on their art — hint at their successes and talk up their brilliance, they fish for compliments and make snide putdowns to put others in their place, while working the room to their best advantage. Art is mentioned as if it is a by-product, merely a name-dropping convenience of what they truely want: attention. And when the dinner is finally served, the actress in her place at the head of the table, with Eugene slobbering over her as he is increasingly wine-fuelled and drug-sniffed, and Nicole sagely nodding and smiling to everything she says until… a conversation that cuts to the heart of the pretension plays out. The actress launches into a heated debate with the arrogant and soon-to-be-cut-down Alexander. Revenge for the narrator is sweet, the actress acting as a vehicle for our narrator’s distaste of the company. Zubno openly takes Thomas Bernhard’s The Woodcutters and brings it to America in the current century, using the same form — one paragraph (not that I noticed until the end) and one evening — and despite the shallow characters creates something clever, ruthless, and reflective. (I’ll be reading the original to compare.)

“A revolutionary book. When Spark published her first novel, The Comforters, in 1957, it was recognised as unique — something that quite simply had never been done before. Wilson's achievement in Electric Spark is equally remarkable: an entirely original method of life writing which leaves conventional biographical techniques gasping in the dust. Electric Spark heaves with ghosts and furies, burglaries and blackmail. It is disquieting and absolutely mesmerising. I was possessed by this book in the same way that I suspect its author was possessed by Spark. It still hasn't put me down.” —Lisa Hilton, Spectator

”Wilson is not any old biographer. Her books are intense, eclectic and wildly diversionary, her intelligence rising from their pages like steam — and in Spark, the cleverest and the weirdest of them all, she may have found her ultimate subject.” —Rachel Cooke, Observer